Note: Originally commissioned by Mary Chesterfield, editor-in-chief, Appellation Magazine, as a feature article for an issue devoted to Portugal; the issue never came to publication

![]()

Cell Phone of Longing

September 13, 1997

For Mary

Introduction

I was traveling in Portugal with my husband, Paulo, to research and write an article about Portuguese fado, when I heard from Appellation Magazine of Mary Chesterfield’s death in a car accident. After the phone call, we went out and walked through the streets of Lisbon, stricken. It was after midnight, which in September can be a very pretty time of the night, when the air is soft and the aqueduct is illuminated like a second moon. Moving through crowds of people on the cobbled streets, we passed a church with statues I have always admired. It’s not one of the notable or famous churches, but that’s how things are here: on nearly every street corner, and down each alley, there is a piece of something, some part of a whole, which speaks.

I looked at the statues hard, as if they had answers. As hard as I looked, they remained graceful and certain, full of yearning and devotion. How is it, I thought, that we make these things which endure, and then we die? It’s so often said that this is the reason we make them, so that something of ourselves will endure after us, but it seems tonight to be so backward, so unreasonable, a kind of dyslexia of the soul.

I am in Lisbon because of Mary, because she saw something in my work and gave me a chance to carry it a little further. I was thinking about this and about the fado. Here, I’ve found a form of music that takes all those confusions, these ironies of life, and makes of them a series of notes and a faltering of the voice that is so expressive, it turns the eyes into fountains.

There’s this great moment that often comes towards the end of a fado. The fadista pauses. The musicians, who have been working with and against her heartbeat—she stands literally between them with a hand on either shoulder—pause, and out of this silence comes a great wail of sound that sets up a sympathetic vibration in the strings of the instruments and can be heard at the farthest corners of the bar.

I sit stunned, understanding that my bones have set up a sympathetic vibration, just as Mary’s life will—now, and into the future—have repercussions that will not leave us lonely. I dedicate this whimsy of 24 hours in Lisbon to Mary.

CELL PHONE OF LONGING: Twenty-four Hours in Lisbon

Day begins in a Lisbon cafe at the moment a cellular phone in the hand of a Portuguese child startles me awake. I am awake to history and to longing, intertwined in the scrolls of steam from a bika of Portuguese espresso.

I have slept just enough to pay homage to the god of dreams, but not so much that the pastries have lost their internal heat. Ordering coffee, I look around and see cell phones everywhere: being used in line while waiting to pay the cashier, tossed in the air, against an ear here or a mouth there, the mouth laughing.

The day opens in front of me, and I can think of no more pleasant duty than to be in Lisbon with the man I love, and to give myself to this city, and allow Lisbon to give back in stone, olive, and guitarra.

Olisipo, this city was called in 60 BC, when it became the western capital of the Roman Empire. Lisboa, city that parades at the edge of the sea, a sea that distorted the very shape of history with its swells. The ocean was forever drawing away sailors, bringing back gold, fishermen—rhythmically—the stiff, dried codfish newly arrived from Iceland hanging in bakery windows. Under foot are the pedrinhas calcado—the little dressed stones—which tick tack beneath high heel shoes, and are said to give way to weeping at the slightest exhibition of sentiment—the merest tenderness of pastry, or phrase of song.

Lisbon is home to hundreds of chapels where candles are lit, begging the Virgin for safe passage for its sailors. It is home to houses of fado music, where laments are sung to absent or drowned lovers, children running from the dictatorship, fathers gone far away in search of work. This element of absence and distance is a particular component of the Portuguese saudades that makes up the yearning of a fado composition.

I rip at the flaky flesh of my croissant and it comes away with a damp and fragrant crackling—whorls of flaky cirrus clouds that melt against the tongue. My espresso arrives: uma bika. I sort change in my pocket, look out at a passing bus advertisement for a television show on the life of Fernando Pessoa, national poet. I mark how far the sun has fissured the sidewalk with shadows.

I survey my cafe with its shining glass counters and display cases set with multitudes of pastries, glistening in their sugar and egg glazes. There are dozens of rows of golden flames, some with tongues of cream sticking out, others with bits of smoked ham emerging, still others covered with almonds or powdered sugar. The sheer variety dazzles, even in the humblest pastelaria: custards and glossy buns with currants sailing over the tops of tiny muffined peaks, the tell-tale orange glow from egg yolks dark as country mustard.

Once ordered, the delicate creations are plucked onto a plate and slung across the counter. The pace is brisk, the attendants professional, singing out their orders to the operator of the espresso machine.

Portuguese convents are credited with developing this artistry with flour, butter (sometimes lard), sugar, and eggs. This legacy is echoed in names of some of the more unusual or decadent pastries: Nuns’ Bellies, Bacon from Heaven, Angels’ Breasts, Abbots’ Ears.

The coming heat of the day is already prickling in the armpits as we walk from the cafe past the Cafe Brasilera, and go to find a book of Fernando Pessoa at Libraria Bertrand—publisher and bookstore in the Chiado district—one of my favorite places to browse literature, art, and history in bilingual editions.

Soon I have Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet tucked under my arm, and I walk to the beat of his descriptive details of everyday happenings, pondering the fact that he calls these incidents of daily Lisbon life formless. I envy his insomnia. I try the music of his language on my tongue. Insomnia would be an asset in this city, where the small hours of the night are equally as fragrant as the late morning.

His words make clear to me why there are alleys criss-crossed by cats, and bolts of freshly baked rustic bread dipped in “green” wine. No matter where I go in Lisbon, his articulate laments trail after me, correcting my metabolism, taking hasty conclusions and rhyming them with unfinished business, turning over each brittle perfection to show its more colorful side.

We descend from the Chiado district on little streets to the Baixa, and shop for a skirt in that mustard color of the Portuguese Rope Factory, then shoes of supple Portuguese leather, and consider linen jackets in impossible shades of pistachio and faded periwinkle.

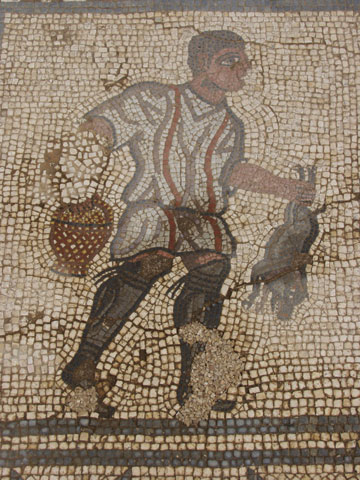

Then we make our way, back up the twisted streets—streets that survived a fatal eighteenth century earthquake that was an order of magnitude higher than the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. We order lunch at Cervejaria da Trindade, a restaurant that first opened its doors in 1836 in a former (thirteenth century) monastery. Under the vaulted roof of the main room we sit surrounded by towering human figures representing Earth, Water, Fire, and Wind, painted in the classic yellow and blue on panels of azulejos, Portuguese tiles heavily cracked and fragmented from earthquakes over the centuries.

The first time I ate Açorda de Marisco here, I became a devoted patron of this place frequented by foreign visitors, locals, young people, lone poets. The dish—a shellfish stew based in bread and garlic broth—is served in a bowl that can be shared by two, and with Vinho Verde, the light, sparkly wine of the north, the early afternoon passes.

Leaving the central area of the city behind for a park, the Jardim de Estrela, we find the rejuvenating quiet and absolute stillness of heat, and lay ourselves down in a secluded grotto to swoon a bit—those brief lapses of consciousness during which a whole hour can pass. If we are lucky, we might see an aranhão, a big spider—one of those eight-limbed human creatures with two heads and two sets of arms, each twined round the other—which inhabit discrete corners of public parks, often near fountains, reminding my companion that there is no place in most crowded family apartments to snuggle with your sweetheart.

Jardim de Estrela is the park where children are fed ice cream and told stories, like the story of the queen, Dona Isabel, who spent much of her time providing food to the poor. The king, Dom Dinis, found her love of the people distasteful and forbade her to go out on the street. She, being sweet-natured, continued in her bad habits. One day, when she was out, distributing bread which she held concealed in her skirts, the king rode up on his horse, furious. “Madam,” he said, “what do you have there?” “Flowers, my Lord,” she replied. He demanded that she show him, and when she opened her skirts, out fell a cascade of white blossoms.

Or you hear the story told in an old song, “Fado do Embuçado,” Fado of the Hooded Figure, which tells of a time when a fadista would come to the taverna each night and sing, always concealing his face under a hood. Finally, one night, a member of the audience demanded that the singer must reveal his identity. After he had sung, and charmed everyone, and left tears standing in many eyes, he lifted his hood, and it was the king himself.

At the moment the street lights come on, we find ourselves in Cascais, west from Lisbon along the Tejo River, where it opens up into the Atlantic Ocean, sitting on the terrace of the Hotel Baia, watching twilight steal the colors of the fishermen’s boats and throw them up into the clouds. Boats and yachts at anchor swing and point upriver. Crowds of people mingle and promenade. Waiters whirl over the marble terrace with their trays tilted at that slight angle that assures us the sky will now finish drinking the light.

A public address system floats the sound check of a band setting up to play an evening open air concert. A hesitant and colorless drum solo is pursued by the wavery notes of a saxophone, and then I sit up, startled, as a singer rises through his notes and pushes back the night. In that brief ascension and crackle of microphone, I hear the Renaissance: whole tones, tangling in mirrors. The bathers, the waiters, the strolling families… everyone in the vicinity behaves as if this was ordinary, merely a local band doing old songs from the villages.

“Green,” he sings, “large moon, and the large guitars.” His voice rings out over the PA system and the heart stops, full of centuries of dust and rivers and gold.

Just as we resolve to stay and hear the concert, down comes an unexpected rain, in fat slow drops that become more rapid until laughter rings out over the terrace and dozens of people scoop up bags, their periodicals and writing equipment. That little phrase of notes becomes a permanent tease, an unfinished concert that has infected me with uncertainty. I will never find out how happy I would have been, or who the singer was. Or what would have happened to my life afterward. Fate.

As we head into the night, driving past old boulevards that lead to the river, we pass the Praça do Commercio, then suddenly left, diving into the Alfama. The streets immediately narrow, the buildings close in.

The Alfama keeps its link to the Moorish inhabitants who were here before the Portuguese. It is close to the harbor. Sailors have always lived here, centuries of sailors longing for the sea, and women longing for their sailors.

The center of the night is spent at small tables listening to the passionate voices of the fadistas, in streets that have never been counted by census. And who’s to say whether or not, during the long hours, a plate of pretty little white beans didn’t arrive at our table, doused with olive oil, or a chorizo, splashed with bagaço, the grape aguardente, and lit on fire? Or a bacalhau, poached gently in cream—leaching out all that saltiness—while the conversation hovers over the end of the dictatorship in 1974, or the curious Auto Palace on the Rua Alexandre Herculano, designed by Eiffel himself during a lost weekend from his native France. The bottles in front of us change color, from the moody red of the Alentejo region to a transparent green that, when tipped, filled us with wine the color of summer grasses, the labels a chant of historical names: Cadaval, Catarina, Fernão Pires, Trincadeira Preta; the presunto covered with a linen napkin on a corner table; all very correct.

From the Alfama we wander to the Bairro Alto district and further, ending up in a room off the aqueduct, where amphora sit in niches lit by blue neon. I am told this is the old counting room, where medieval Lisboans were summoned to pay their taxes, with the encouragement of chains and maces. In the venerable stone room, women dressed in medieval costumes carry plates of flaming chorizo above their heads as they make their way along the rows of linen-covered tables. Fadistas and their musicians and friends come here to gossip, sing, eat, smoke. Faces come and go; small dramas unfold in in all directions. There is much bantering; stories unfold that speed up the precious remaining hour of the night, and slow down the pulse.

Before we realize it, the night is over. Taxis are called. We step out into the dawn, and pass through a quiet city, the streets just starting to come awake, and park next to the Tejo. Trucks and cars are double parked. A steady flux of people are preparing for the morning market.

Evening ends at the waterfront at dawn, with slow sips of Longshoreman’s coffee and their dense pastry like communion wafers; the sky arching away from night, lifting the top of the head off, as the body starts to come down from the baptism of the night’s voices. We stand at the counter with our feet in the sawdust, and suckle on the little bikas. My mind begins to blink. All around us is the bustle of the grand marketplace, a palace of produce, fish, and pig’s trotters; flowers from all over Portugal and the world; stalls of hams, cheeses, and fruits arrayed in pyramids.

Perhaps somewhere in Pessoa’s notes there is a passage which explains why our hearts falter at old stone and old sorrows, why we are always making them new again. Until then, I will have to return to this corner of the world and reset my Portuguese clock of twenty-four hours, which ends with a cell phone in the hand of a pedestrian crossing the trolley tracks at dawn in front of the Mercado.

Copyright © 1997 Theresa Whitehill, All Rights Reserved